The Problem

Intimate partner violence (IPV) isn’t a rare event; it’s a repeated-contact problem that police and advocates see over and over, often before the most dangerous escalation happens. Yet many systems still rely on short checklists and officer judgment to decide who gets urgent safety planning, shelter linkage, or intensive follow‑up.

Those traditional approaches can miss the people most likely to face severe or near‑fatal violence, while also flagging many who won’t escalate (which consumes scarce advocate time and burns out responders). The result is a painful mismatch: the highest-risk cases are hard to spot, but the “high risk” label is handed out in a way that isn’t reliably tied to outcomes.

A data science approach is straightforward in principle: combine prior incident histories, known risk factors, and patterns in repeat calls to predict who is most likely to experience serious harm (or to reoffend) and then focus resources where they change outcomes most. The implementation reality, though, is far messier than building a model with a decent AUC.

What Research Shows

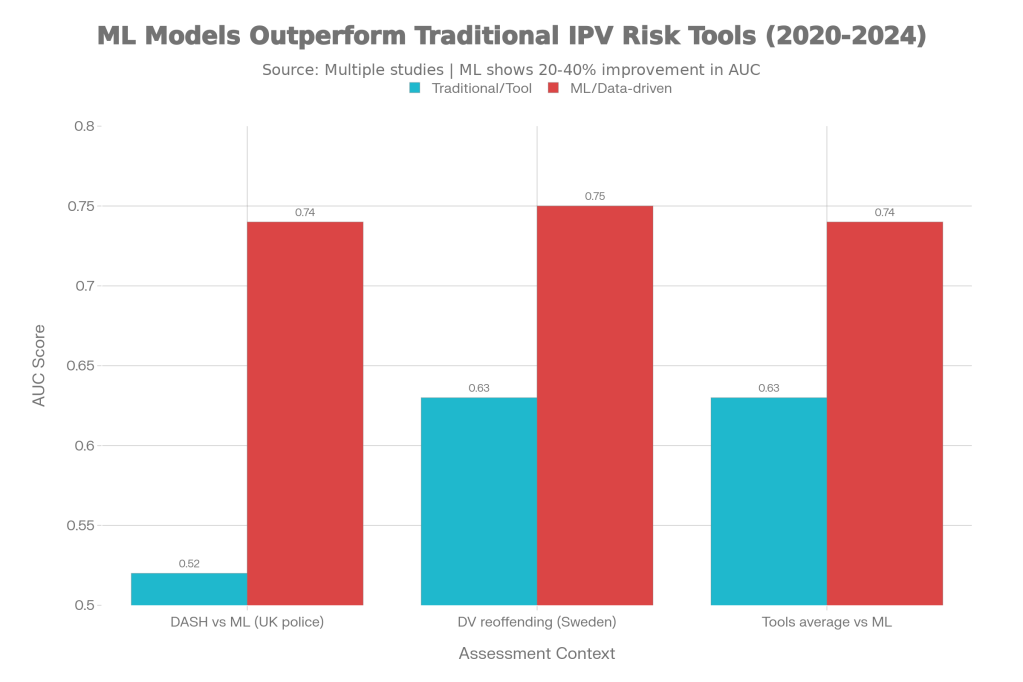

The evidence that “business as usual” risk assessment is weak is blunt. In the UK, research on the DASH domestic abuse risk assessment found that officer risk predictions were only slightly better than chance, with AUC around 0.52 in one major evaluation. That means the tool’s ranking of who is “more likely” vs “less likely” to recontact or reoffend can be close to random in practice.

In the same domain, machine learning and modern statistical learning methods do much better when trained on operational police data. A 2022 study on police domestic abuse risk assessment tested multiple machine learning approaches and reported substantially higher discriminative performance (reported via AUC) than officer judgment. In other words, the data already sitting in police systems often contains enough signal to meaningfully improve risk ranking—if it’s modeled well.

This pattern—actuarial/data-driven methods outperforming unstructured judgment—shows up across violence risk prediction. A 2024 systematic review focused on IPV risk assessment tools summarized that these tools often land around AUC ≈ 0.63, which is meaningfully above chance but still not strong for high-stakes decisions about victim safety. That’s the space where machine learning is most promising: not “perfect prediction,” but better triage under limited staffing and time.

Chart 1: Accuracy vs traditional approaches

Predictive accuracy (AUC) for IPV/domestic abuse risk: traditional tools/assessments vs data-driven models

What the Real World Shows

One of the most concrete “real-world outcomes” interventions is the Lethality Assessment Program (LAP), which pairs a brief on-scene lethality screen with an immediate connection to a hotline/advocate for people flagged as high danger. In a multi-jurisdiction evaluation in Oklahoma, 648 women were interviewed during the intervention phase, and 347 (53.5%) screened as high danger and spoke with a hotline counselor as part of the protocol. The evaluation reported improvements in safety planning and help-seeking behaviors and reductions in the severity/frequency of violence among participants at follow-up (median ~7 months), even when changes in overall frequency were harder to detect.

There is also emerging evidence that information + targeted safety action can reduce lethal outcomes at population scale. A 2024 economics paper reported that LAP reduced female homicides committed by men by about 40% in the studied setting, framing LAP as a victim-focused policing intervention where risk awareness and safety planning is concentrated on the most at-risk victims. That’s an unusually direct “hard outcome” signal in a field where randomized lethal-violence trials are ethically and practically difficult.

At the same time, implementation fidelity is inconsistent, and that inconsistency matters. A 2025 audit of the Dallas Police Department’s domestic violence efforts reported that the share of high-risk victims who immediately spoke with a shelter/counselor on scene was around 20% during the audit period (and noted this represented a decline), showing how easily the “connect to help right now” step breaks down in practice.

The Implementation Gap

The first gap is accuracy-to-action: many IPV tools produce mediocre discrimination, so frontline staff learn (rationally) not to trust them. When “high risk” doesn’t reliably predict near-term harm, responders either overreact (over-referral) or tune out alerts entirely. This is the same failure mode seen in other alerting systems: weak signal plus high workload leads to alert fatigue.

The second gap is workflow reliability. LAP is intentionally simple, but it still requires officers to administer the screen, classify risk, and complete a warm handoff to an advocate while on scene. The Dallas audit’s ~20% immediate connection rate for high-risk cases illustrates the operational friction: staffing constraints, time pressure, missed calls, technology issues, and uneven training can collapse the key step that makes the program more than a checklist.

The third gap is governance and trust around predictive models. “Predicting Domestic Abuse (Fairly)” research explicitly engages fairness concerns, because models trained on police data can reflect patterns of enforcement and reporting, not just underlying violence. Agencies fear deploying a model that could be perceived as biased, hard to explain, or legally risky—especially when decisions involve resource allocation and potential coercive interventions.

The fourth gap is that many systems optimize for the wrong metric. A tool can achieve a better AUC and still fail operationally if it generates too many false positives for the available advocate capacity, or if it identifies risk without a guaranteed intervention slot (shelter bed, protective order support, relocation funds, etc.). Prediction without capacity turns “risk identification” into another frustrating conversation with a victim who is told they are in danger but offered limited concrete help.

Where It Actually Works

LAP tends to work best where the on-scene handoff is treated as a core performance requirement and where hotlines/advocates are resourced to answer immediately and continue follow-up. The Oklahoma evaluation design highlights this: the intervention wasn’t just a score; it was a tightly defined protocol linking screening to immediate counseling and safety planning.

Data-driven approaches also fit better when agencies make them decision-support rather than decision-making. The fairness-focused police risk assessment work emphasizes careful model evaluation and responsible use, which improves buy-in and reduces the chance the tool is used as an opaque justification for punitive actions.

The Opportunity

Better IPV prediction is already technically achievable; the high-impact move is making prediction reliably trigger the right help at the right time.

- Validate models locally and monitor drift so risk scores stay calibrated to real outcomes over time.

- Build “capacity-aware” thresholds (who gets a call today) to prevent false-positive overload and alert fatigue.

- Measure implementation fidelity (screen completion, warm handoff rate, advocate contact time) as seriously as model AUC.

- Use interpretable, fairness-audited models and publish governance rules to build legitimacy with communities and staff.

- Pair high-risk identification with guaranteed intervention pathways (rapid relocation funds, protective-order navigation, shelter priority) so risk detection isn’t a dead end.

References (numbered)

Fjeldsted, A., et al. “Predicting Domestic Abuse (Fairly) and Police Risk Assessment.” PNAS Nexus / open-access via PMC, 2022.

Bland, M., et al. “Dashing Hopes? The Predictive Accuracy of Domestic Abuse Risk Assessment by Police.” British Journal of Criminology, 2019.

Nilsson, T., et al. “Development and Validation of a Prediction Tool for Reoffending Outcomes in Individuals Arrested for Domestic Violence.” JAMA Network Open, 2023.

National Institute of Justice. “How Effective Are Lethality Assessment Programs for Addressing Intimate Partner Violence?” 2018 summary of quasi-experimental evaluation findings.

Messing, J., et al. “Police Departments’ Use of the Lethality Assessment Program” (NIJ report; includes sample counts and implementation details; 648 interviewed, 347 high danger connected). 2015.

“Can information save lives? Effect of a victim-focused police … (LAP).” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2024 (reports ~40% reduction in female homicides by men).

Dallas City Auditor. “Audit of Dallas Police Department’s Efforts to Protect Victims of Domestic Violence.” 2025 (reports ~20% on-scene counselor connection for high-risk victims during audit period).

Domestic Violence Resource & Information Center (DVRIC). “Intimate Partner Violence and Risk Assessment: A Systematic Review.” 2024 (summarizes typical AUC around 0.63 for IPV risk tools).

Boserup, B., et al. “Lethality assessment protocol: Challenges and barriers…” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2024 (implementation barriers).

If a different domain is preferred (not criminal justice / policing-adjacent), name one constraint (e.g., “must be workplace safety,” “must be elections,” “must be water infrastructure”), and a new topic can be built with the same structure and charts.

Leave a comment